Genomics of the vector of EEE virus, Culiseta melanura

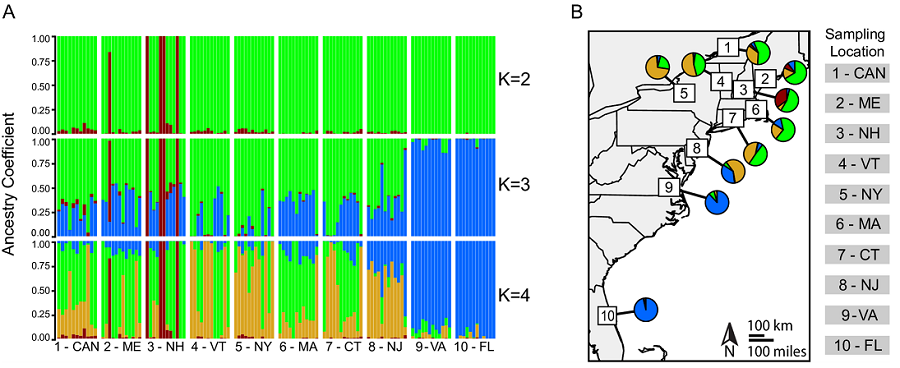

The disease vector Culiseta melanura occupies wetland habitats throughout eastern North America. This species plays an important role in Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus transmission, and observations on host association (e.g. from bloodmeal analyses) suggest feeding patterns vary by geographic location, and are not always related to host abundances. Recently, colleagues and I have published the first genetic - and genomic - study of this mosquito. I present one figure from our manuscript above, which plots the four genetic clusters we found geographically. There is a clear pattern of transition from south to north between clusters, but a lot of mixing in northern sites, which I discuss a bit below. Previous to our work, only limited Sanger sequencing had been performed on this mosquito targetting cytochrome oxidase for barcoding and ribosomal RNA genes for single gene phylogenetics. The full text is available freely from PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases.1

A New Mosquito Draft Genome

As part of this project, to serve both as a reference for population genomics and for future research efforts to understand underlying variation in host feeding patterns, I decided to sequence a draft genome using Pacific Bioscience’s long read SMRT Sequencing. Because mosquito genomes are highly repetitive, particularly in the subfamily to which Culiseta belongs, short reads are typically insufficient to assemble contiguous genomes.

Sequencing of more than 20 SMRT cells yielded a ~1.3 gigabase draft genome with a contig N50 of 90 kb. This genome size was similar to previous estimates from cytophotometry. Following polishing, the genome had nearly 90% of single copy ortholgos present in some way, and was approximately equivalent in completeness to many other publicly available vector genomes. We hope to return to this genome some day and perform additional sequencing. For a first effort, and in an organism where the most sequencing previously attempted was cytochrome oxidase and ribosomal RNA genes, we were extremely happy with these results.

Population Genomics of Culiseta melanura

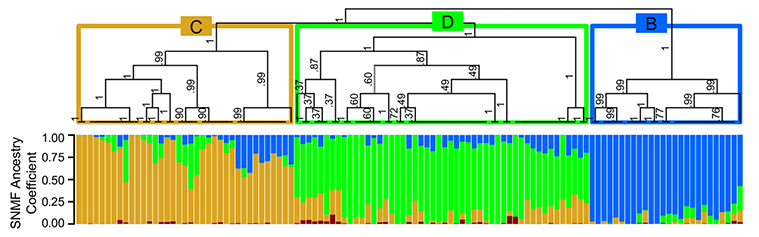

Next, we gathered samples from 10 sites across eastern North America, with a particular focus on the northeastern United States. We used two common cutting enzymes, along with double digest RADseq, and generated data from 12 individuals from each population. Our reference genome allowed us to capture more SNPs from more individuals than we would have otherwise, and it also aided significantly in filtering linked sites. In the future, it may even aid us in detecting outlier loci and signatures of selection. For now, our analyses have focused only on the structure and connectivity of the populations we sampled. Below, I present a few such analyses, including STRUCTURE-like analyses (where each bar is an individual), an associated phylogenetic tree demonstrating relationships between major clusters (made from fineRADstructure - see the publication for details), and finally, an assignment test with DAPC. First, the tree and STRUCTURE-like SNMF results:

We used LEA to perform a STRUCTURE-like SNMF analysis, and found multiple genetic clusters, with the best-supported ancestral clusters being four clusters. The first and more ancestral cluster (B and blue in the figures here) was associated with southern sampling sites and New Jersey. We believe this cluster represents an ancestral cluster in eastern North America - it is the most diverse genetic cluster and, in our phylogenomic analyses, also resolved basal to all other clusters (shown above).

The two other major genetic clusters were interspersed among sampling sites in a way that indicated significant connectivity between northern populations of this mosquito. Thus, although these mosquitoes occupy disjunct forested wetland habitats, there appears to be a high degree of gene flow among populations (we think this is real gene flow, too, and not just ancestral polymorphism - we discuss that more in our paper). This factor may limit the effectiveness of local control efforts aimed at eliminating this vector species.

Perhaps most interestingly, we found evidence of a cryptic, distinct cluster with a huge number of private - or uniquely shared in that cluster - alleles (red in the above figures). Individuals belonging predominantly to this cluster - a total of 5 such mosquitoes from two sites - had three to six times more private alleles than did populations geographically close to them and more than twice the number of such loci as southern, ‘ancestral’ populations. We confirmed our previous morphological identification of these individuals as Cs. melanura with cytochrome oxidase barcoding. I wonder if these results aren’t evidence of some hybridization with a closely related species, or a cryptic subspecies… For now, though, we are left only with speculation, as the limited genetic data available for this genus precludes further investigation.

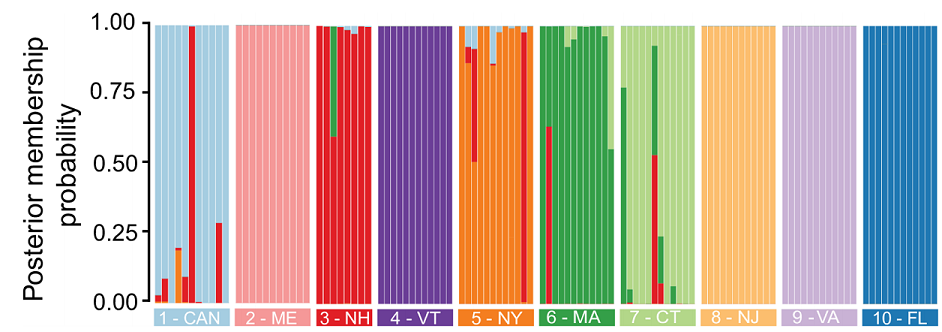

It is worth noting that although we found strong evidence of gene flow between populations, we also had evidence of some degree of differentiation between populations. In addition to significant pairwise Fst values between populations, we were able to use Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components to assign back the majority of individuals to their populations of origin, demonstrating that there were consistent underlying differences between individuals that could be used to place them reliably with conspecifics sampled at the same location:

Although I am moving on from this system for now, I hope to return to it some day, and improve the genomic resources I created and try to figure out what exactly is happening with Cs. melanura in New Hampshire, Canada, and Maine - the locales we detected the greatest evidence of the cryptic genetic lineage I described above. For a much more thorough discussion of these results, check out my paper, recently published in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases: